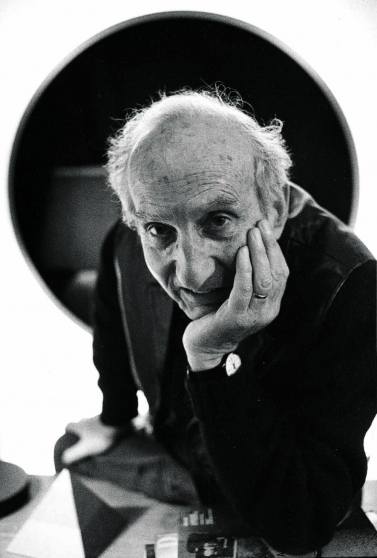

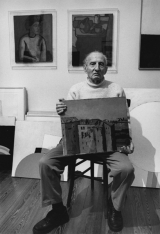

Eugenio Carmi (b. Genoa, 17 February 1920 - d. Lugano, 16 February 2016) has been a leading exponent of Italian abstract art since the early 1950s. For two decades he devoted himself to Art Informel and, from the end of the 1960s onwards, he adopted the rigour of geometrical forms, which he gradually developed over the following decades. Although the majority of his works are paintings on canvas, his works on paper, those made with iron and tin plate, multiples and sculptures are also important. He made two kinetic works; it was thanks to one of these, SPCE, that he was invited to participate in the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966. From 1956 to 1965 he was artistic consultant to the Italsider steelworks (located in Cornigliano, on the outskirts of Genoa) and in 1963 founded the Galleria del Deposito. A member of the Alliance Graphique International, he is still regarded as one of the innovators of the language of graphic arts in the 1950s and 1960s. Over the years, the daily constant of the painting he has produced in his studio has never been a purely personal matter. Always in contact with the world and other people — assistants or other artists and intellectuals of international standing — he has often played a leading role with the ability to catalyse talent. Eugenio Carmi has never ceased to intervene in the world: first of all with his art, also verbally with an active presence in international meetings and conferences and through teaching. His friendship and collaboration with Umberto Eco resulted in the creation of three fairy tales — subsequently translated into many different languages — and Stripsody, a work that owes its unique quality to the profound harmony in artistic and human terms between him, Eco and the American mezzo-soprano and composer Cathy Berberian. Over the years, Carmi has shown his works in numerous solo exhibitions in Italy and elsewhere. His works are to be found in collections of museums and institutions in Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, Poland and the United States. Since 1971 he has lived in Milan. He describes himself as an ‘image-maker’.

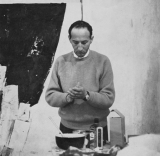

Eugenio Carmi was born in Genoa on 17 February 1920 and, when he started to paint at the age of fifteen, he was already taking his first painting lessons. From 1938 onwards he lived in Switzerland, firstly in Zug, where he completed his secondary education at an Italian boarding school and then in Zurich, where he stayed until the end of the Second World War, graduating in chemistry at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule or ETH). In the cosmopolitan city of Zurich he came into contact with its stimulating cultural and artistic milieu, and it was here that he started to appreciate the work of the leading exponents of twentieth-century abstract art. Together with a group of expatriate students, he founded a club dedicated to the antifascist intellectual Piero Gobetti. When he returned to Italy after the end of the war he resumed his artistic studies, in 1946 in Genoa under the guidance of the sculptor Guido Galletti and, in 1947 and 1948, in Turin as a pupil of the painter Felice Casorati, whom he had encountered during a lecture and series of lessons in Genoa. He continued to be inspired by Casorati’s work until the beginning of the 1950s, when his painting evolved from a figurative to a non-representational style and he started to produce collages and works on paper as well as those on canvas. In 1945 he met the young artist Kiky Vices Vinci, who, although she was born in Naples, had grown up in Genoa. They shared a passion for literature and films and, above all, art, especially painting. As they went round Genoa, they drew and painted their city, which still bore signs of wartime damage, with views expressing its atmosphere on small canvases and paper that, although still figurative, heralded the abstraction yet to come. They married in 1950 and, in 1956, moved with their first daughter, Francesca, to Boccadasse, an old fishing village located on the edge of Genoa, where Antonia, Stefano and Valentina were born. Here he set up his first painting studio, while, at the same time, he worked as a graphic designer and, in 1954, became a member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale. Throughout his artistic career, Carmi has continued to focus on painting, the sine qua non of his creative practice. Every day he is at work in his studio, dividing his time between painting and the other professional commitments to which he has devoted himself with infectious enthusiasm.

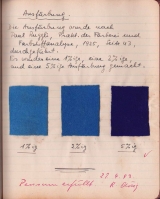

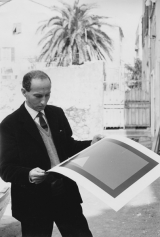

From 1956 to 1965, when Carmi was given the task of promoting the image of the Cornigliano (later Italsider) steelworks, he brought contemporary art into the factory, coordinating the visual and cultural elements that served to enhance the firm’s corporate identity. In this period, iron and steel became an important artistic stimulus for him: in 1958 the critic Gillo Dorfles organized his first solo exhibition at the Galleria Numero in Florence with enamel paintings on steel. From 1960 onwards he executed works in welded iron and steel (including the Appunti sul nostro tempo [Notes on Our Times] series) and, from 1964 onwards, lithographs on tin plate. This was a period when he struck up friendships with numerous artists and intellectuals — for instance, Victor Vasarely, Umberto Eco, Max Bill, Konrad Wachsmann, Furio Colombo, Ugo Mulas, Kurt Blum, Emanuele Luzzati and Flavio Costantini — and collaborated with other creative figures. In 1963 he founded the Galleria del Deposito, which, with his multiples (1967–69), was intended to offer art accessible to a wider public. In 1966 he illustrated fairy tales by Umberto Eco, which were published by Bompiani; republished in 1988 with new illustrations and, in 1992, the addition of a third story, these were then translated into many different languages. In 1966 he also produced the illustrations for Stripsody, a musical work based on the onomatopoeic sounds of comic strips conceived and interpreted by Cathy Berberian. Inspired by the growing interest in technology, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he experimented with kinetic and audiovisual art and also created the imaginary electric signs that were to be at the centre of a provocative installation in the streets of the Caorle, a small town on the coast near Venice. In the same year he participated in the 33rd Venice Biennale with the electronic work entitled SPCE (‘struttura policiclica a controllo elettronico’ [‘electronically controlled polycyclic structure’]), which resulted in the critic Pierre Restany inviting him to show his electronic works at the Superlund exhibition in Sweden in 1967.

While in the 1960s and 1970s his artistic work was often closely linked to projects and initiatives in the industrial and cultural worlds, in the following decades Carmi focused primarily on working in his studio, which, in the meanwhile, he had moved in Milan (in 1971). Despite occasional forays into other parallel fields, such as the creation of mirrors and stained glass, painting and, more rarely, sculpture — which he had first become interested in when working for Italsider — were his principal activities. And it was at the beginning of the 1970 that he developed the geometric style he had already employed a number of times before (accident prevention signs for Italsider, multiples for the Galleria del Deposito and the Imaginary electric signs), replacing the Art Informel style of the two previous decades. From the 1980s onwards he started using jute as a support, foreshadowing his subsequent return to emphasis on the materials used. His art evolved gradually but continuously with rigour and consistency. Also through geometric abstraction, his archetypal forms came increasingly closer to a relationship with spirituality, thanks to the use, however, of more sensual, natural materials. Umberto Eco described him as ‘an eminently urban creature’ in his book Carmi, una pittura di paesaggio (Carmi: landscape painting?). He continued to be an urban creature in the following decades, but, in his later works, there has been a radical change of course. In recent years, ‘the image maker’ — as he styles himself — has engaged in a continuous dialogue with nature, as represented by its mathematical laws. Pythagoras’s theorem and the golden section were his keys to entering nature and celebrating it, together with a further change of direction: the geometric forms were now much more closely related to the materials used and thus alluded to his Art Informel works of the 1950s and 1960s, as in a circular dialogue. And, in this imaginary circle, his mathematical training when he was studying at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich should not be underestimated. In these years, too, critics and intellectuals who shared his aesthetic and social vision wrote about him. A constant presence in this period has been his passion for teaching, for which he developed a keen interest in 1973 in the United States, when he held seminars at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. In 1990 the municipality of Milan staged a retrospective exhibition of his work, curated by Luciano Caramel, at the Padiglione Rosso of the city’s Spazio Ansaldo. In 1992, another exhibition devoted to him was held at the Historical Museum of the Royal Palace in Budapest and, in 2000, he was invited to display his current work at the Chamber of Deputies in Rome.

In his long career, Carmi has had exhibitions in leading European and American galleries, as well as in a number of European museums and various Italian Cultural Institutes abroad. In 2011 he participated in the Venice Biennale for the second time. He has received international prizes and acclaim for painting and graphic design, he held seminars on the visual arts at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence in the United States and, in the 1970s he taught at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Macerata and the Accademia di Belle Arti in Ravenna. Over the years he has taken an active part in international conferences and, thanks to his understanding of the world of children, he was invited by primary school teachers to talk to their pupils. In 2001 he was elected a member of the Accademia di San Luca. Often commissioned by public and private institutions, aquatints and screen prints were made after his original works. He used to describe himself as an ‘image-maker’.